The early 20th century Irish poet William Butler Yeats was in a creative rut later in his life. But then his new bride Georgie started doing something called automatic writing and he became convinced she was some kind of spiritual medium, tapping into all the secrets of the cosmos. Yeats used her automatic writings as the basis of a new vision of history as this series of interlocking masks and gyres. He also developed a personal system of symbols based on Georgie's automatic writings. And all this weirdness led to his absolutely greatest works.

Was Georgie actually tapping into some greater plane? Was she caught up in some honeymoon poetic excitability? Or was she just pretending to be a medium in order to make sure her easily distracted husband — famously in love with both his old flame Maud Gonne as well as Maud Gonne's daughter — would keep paying attention to her? Who cares. The automatic writings and the symbolism and the self-certainty and inspiration Yeats gathered from it all led to him writing his best poems.

When it comes to whatever principles or theories or schools of thought inform someone's writing, it doesn't matter if it's "right." It only matters if that theory or method leads a writer to their best work. Any port in a storm.

I'm a creative pragmatist. So my big screenwriting theory is this: shit either works or it doesn't. You can get so fixated on principles and rules and good intentions that you can forget to react to what's happening in front of you.

Many of my colleagues do what is sometimes called a vomit draft. That is, they quickly get all the scenes down quickly with placeholder dialogue so they can have the whole story written out. After this, they go back in and improve the dialogue and take out cliches, etc. And if doing that leads them to their best work, then please for God's sake, they should keep it up.

Simpsons writer John Swartzwelder ably articulates the benefits of this particular approach:

It sound great! Only problem: such an approach doesn't lead me to my best work. I’ve tried it. And sometimes I’m kinda forced into using it. But in ideal conditions, when I write my first draft, I'm not vomiting story beats. Instead, I'm delicately barfing up dramatic moments and surprises.

From scene one, I'm trying to create a dramatic sensation in the reader. And by reader, I mean myself. I want to feel anxious and uncertain and excited to see what happens next. In that first pass, I'm not even telling a story so much as I'm trying to create a continual dramatic tingle that I can then manipulate and maintain on a page by page basis.

To define that dramatic tingle, I'll refer to Alexander Mackendrick's definition of drama from his On-Filmmaking book: "Drama is anticipation mingled with uncertainty."

That feeling of drama in a reader is what I'm trying to generate in my first draft. Then in revisions I go back in and make adjustments to make sure the plot and the characters and the emotions have inner integrity. I'll re-emphasize or de-emphasize beats, cut out a lot of extra fat. I'll also better set things up that happen later in the script, or pay off things that happened earlier.

But in that first draft, I'm trying to find moments and I'm trying to conjure feelings. And all of that feeds into that tingle.

Analogy alert: when I'm working on set during production, I'll sometimes see actors come in with a very fixed idea about how a scene is going to go. They have a game plan and they come in and they execute it. And maybe that sounds good.

But inevitably, these scenes almost always end up a disappointment. The game plan actor usually isn't listening or responding to their scene partners. Even worse, they aren't responding to their own performance or the energy being created. They're executing their intentions and aren't allowing themselves the space to surprise themselves.

For me, to vomit out scenes with placeholder dialogue, or even to work out every story beat in an outline before I actually write the scenes: that would be like being an actor walking onto set with a game plan to execute. Sure, I might execute the game plan. But I'd also whistle right past every opportunity to do something fresh and unexpected and surprising while doing so.

So what do I do? I don’t walk into a scene empty-handed. I try to know what my characters want out of the scene. And what I want out out of a scene. And loosely what a reader is expecting out of the scene, based on the story’s genre.

With those tools in hand, then I go in and I just improvise, in character, until I feel a tingle. I find that letting my characters surprise me in what they say and what they do and in how they react to each other in the initial pass usually results in my best dialogue.

But it also often results in me realizing that my intentions for the scene were misguided or limited in some way. Or realizing that I'd conceived of a character in a boring way. This more improvisation- and riff-based working method forces me to actually listen to the scene and react to it.

If I did a vomit pass, I'd feel like I was missing out on entire worlds of tingle-creating possibilities. Even in a first draft I don't want my characters very boringly just spill out their thoughts and feelings in order to keep the plot moving or to establish some key piece of information or motivation, because maybe one of those just-move-the-plot-along scenes could've also been the weirdly memorable scene where a minor character unexpectedly breaks your heart.

I think other writers still find those moments in the revisions process. For me, I tend to find them more on my first pass.

There are dangers in my method as well. Mostly, that my characters will jabber on and on with no seeming point and no seeming inner urgency or inner conflict. And this can very easily happen if I don't yet fully understand the real drama or emotion of the scene.

But a boring scene can also happen if I haven't yet established the language games being played by the characters.

"Language game" is the term I use for this: what is this character's unique relationship to the words he or she speaks? What role are they speaking now, either for themselves or for others? What mask do they wear via their dialogue? What inner conversation are they having with their words?

If I can’t answer these questions to myself, then chances are I’ve got a generic character on my hands.

Here are some characters I’ve written for with well-defined language games. And therefore, they were among my favorite characters to have ever written dialogue for. (It also didn’t hurt that each of the performers embodied these characters brilliantly.)

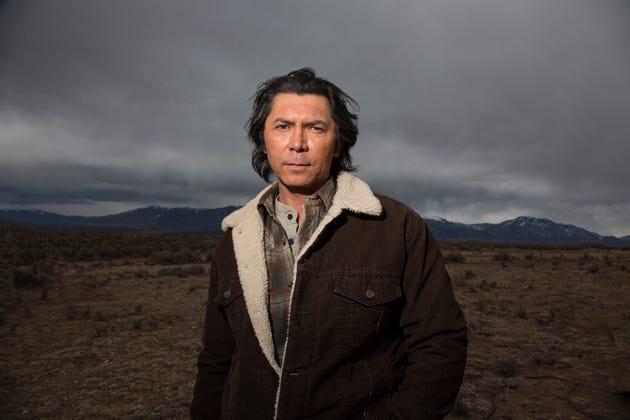

When writing for LONGMIRE, I'd tell myself that Henry Standing Bear's language game was this: he is gonna speak the white man's language with more precision and exactitude than any white man could ever manage. Especially in an emotionally-charged situation. Which feeds into Henry's deadpan demeanor — if he can tightly control his words, he can control his emotions, and not give other people emotional leverage. (Whether this is what my showrunners intended, or how Lou Diamond Phillips thought of Henry's dialogue, I don't know. But it gave me a central throughline when I was writing Henry scenes that I could always tune my writing to.)

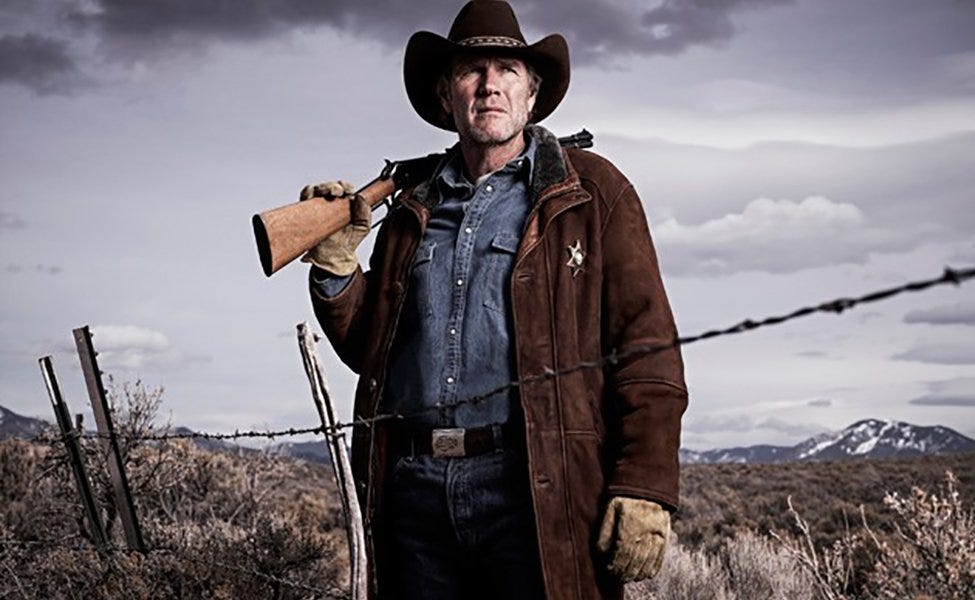

By contrast, Sheriff Walt Longmire tends to be very laconic. More comfortable with silence, he uses as few words as possible. And though he's very well-read and clever — he's a bit of a cowboy Sherlock Holmes — Walt prefers an earthy diction to a bookish one. There's often a paragraph implied with any two-word monosyllabic sentence. Walt just can't bring himself to say that entire paragraph. Even when the situation seems to call for it. He's just not that type of dude. Once I figured this out explicitly — mostly learned by being attentive to Robert Taylor's way of performing scenes — then I better knew how to approach Walt's language game. And how to modulate it on a scene-by-scene basis. And how to invent new guest characters specifically designed to frustrate Walt’s language game for dramatic effect.

On DAMNATION, Connie Nunn reinvented herself as a cold-blooded killer in order to avenge the deaths of her husband and child. But in order to keep her lethal intentions hidden, she's created a strategic language game. Connie plays up the part of the polite, gracious, well-behaved woman so everyone around her will underestimate her. She aggressively blends into the social order in order to be hidden in plain sight. So although she always has murder on her mind, she speaks and behaves with the finest etiquette.

So, that’s what I mean by language game. Basically, a philosophy of speaking uniquely tailored to each character. And I find that it helps to explicitly describe that game.

Once I know a character's unique language game, I can put them in situations where that language game is either a help or a hindrance. Or I can match them up with other characters with a competing language game. And often, that's when sparks fly.

A scene where a laconic cowboy's daughter desperately wants him to comfort her with loving words: will he figure out how to do this? Or a scene where an aggressively polite and self-controlled killer suddenly comes face to face with the man she suspects to be her husband's killer: will her carefully-maintained mask suddenly slip, revealing her ploy before she discovers the truth? And so on.

Those are usually my favorite scenes to write, scenes where a character's language game is incompatible with their current situation.

But first I have to know that language game. If I don't, then what a character is saying is mostly just dictated by his or her current dramatic situation. And in that way, that character is interchangeable with any other character. And I think that's what we mean by a character's dialogue being generic: if any other character would say the same thing in this dramatic situation, then the character isn't well-defined enough. The character isn't bringing enough of their own baggage to the scene.

When I find that my dialogue is underwhelming me, it's usually because the characters are only speaking situation-dependent words. There's no unique language game being played, no underlying battle or seduction or negotiation or subterfuge going on. So the words are thin and the characters interchangeable. When that's the case, I usually need to go back in and create a specific language game for at least one of the characters.

Maybe that means a run-of-the-mill drug smuggler needs to also become an evangelical Christian who tries to convert his criminal cohorts while giving them info about an upcoming drug deal. Or it means a run-of-the-mill police officer interrogating a murder suspects needs to also have just found out that his beloved wife is divorcing him, that way he's trying to keep himself from collapsing into tears during the interrogation.

In both cases, the language game of religious conversion or emotional self-denial can become the focus of the scene. The important exposition can still get across, but now it's riding along with the more interesting character-based dialogue.

Of course, different stories call for different tonalities — if your script is tuned more to NOMADLAND than to say THE BIG LEBOWSKI, then evangelical drug smugglers and heartbroken police officers probably don't make sense for you. But those types of characters fit well in the types of scripts I like to write.

Here's another analogy: the dramatic situation of each scene is like a dance floor that's been built for the characters. That takes planning and forethought. But the dialogue and interactions of the characters in the scene itself is the dance that takes place on that floor. For me, that dance tends to be more of a moment-by-moment improvisation. And I don’t like to rush through it.

If what my characters are doing in a scene isn't very interesting, it often means the characters' words and actions are overly defined by the scene's current situation. They aren't bringing their own individual dance to the scene. Usually, that means I need to revise one or more of the characters so that when they do find themselves in a dramatic situation, that situation isn't the only thing on the tip of their tongues.

This is really good, easy to understand advice on writing characters that pop. Thank you!

Gonna pile on to the compliments here Tony. Your newsletter gives more clarity than a stack of scriptwriting "How-To's", with a real-time, real "industry" techniques that are so relevant and helpful for anyone approaching this as an outsider. Keep it up, please.