The System Is Rigged

as an outsider, can you flip that to your advantage?

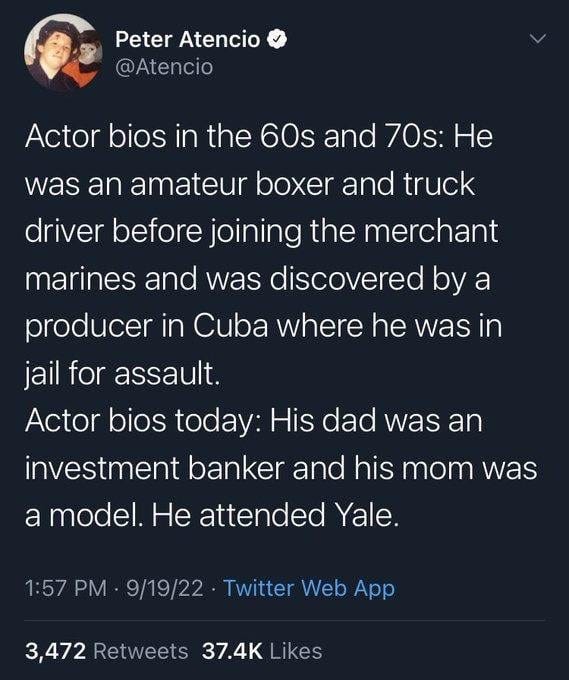

Sometimes Hollywood people say things like the cream rises to the top, but what they fail to mention is that you usually have to be born in the bucket of milk first. I mean, if you’re even half-following announcements on Deadline, it seems like every other “new voice” is the child of someone already perched atop the economic food chain.

You can see this dynamic happening in the world of youth athletics as well. Sports like rowing or tennis or golf were always “rich kid” sports, but now basketball and baseball are like that too. There’s a certain unstated financial entrance fee at work—if your parents can’t afford to get you specialized training at an early age and/or onto AAU or travel teams, you can’t really compete with the kids who can.

I would say that the same affluent drift is now occurring in Hollywood, but I’m pretty sure it’s been happening for decades.

For instance, David Milch is probably my favorite living screenwriter. Turns out, he's the son of a prominent surgeon. Okay, no big deal. Milch is a genius regardless of his background. But Aaron Sorkin is the son of a copyright lawyer. And Shonda Rhimes’ mother was a college professor and her father was an administrator at USC, where Matthew Weiner's father was the chair of the neurology department as a big time doctor.

Issa Rae's father's also a doctor. Callie Khouri's as well. And Veena Sud's. Lena Dunham's parents are pretty famous NYC artists. James Mangold’s parents: also acclaimed visual artists. Beau Willimon's dad: lawyer. Same with Michael Schur's. Damon Lindelof’s dad is a bank manager. Billy Ray: literary agent.

Joss Whedon's father and grandfather were both successful TV writers. JJ Abrams' father was an Emmy-nominated TV producer. Tony and Dan Gilroy’s father was a Pulitzer Prize winning playwright. Noah Baumbach’s parents were notable fiction writers and academics. Damien Chazelle’s father is a Princeton professor. David O. Russell’s father was vice-president of a big New York literary publishing house.

I’m pretty sure Julian Fellowes — the Downton Abbey guy — is like some kind of aristocratic British baron. And Emerald Fennell’s 18th birthday was apparently documented by British high-society journalists. Admittedly, I don’t understand British culture, but that sounds pretty ritzy.

David Benioff’s dad is a Goldman Sachs billionaire. Gifted screenwriter Peter Craig — Top Gun: Maverick, The Batman, The Town, etc — is the son of Sally Field. Mike White’s mother was the executive director of the Pasadena Playhouse and his father wrote speeches for Jerry Falwell. Mike Mills’ father was an art historian and museum director. Alex Garland’s father is a notable political cartoonist and his grandfather was a Nobel-winning biologist. Brad Ingelsby’s father played in the NBA.

David Simon, champion of the American working man, is the son of a prominent public relations director. Chloé Zhao — whose Nomadland documented the struggles of the displaced American underclass to much acclaim — has publicly disputed claims that her steel executive father is a billionaire.

Sofia Coppola’s father made The Godfather. Sam Levinson’s dad made Rain Man. Max Landis’ father made The Blues Brothers. Brandon Cronenberg’s father made Videodrome. Jake Kasdan’s father made The Big Chill and wrote Raiders of the Lost Ark. Jason Reitman’s father directed the original Ghostbusters years before Jason himself directed the most recent iteration, Ghostbusters: Afterlife.

Judd Apatow's dad was a real estate developer and his mom ran a record label. Judd’s daughter Maude recently wrapped directing her first film, which stars her mother, plus the son of a legendary Oscar-winning actor, the daughter of Canadian country music stars, and the daughter of an Emmy-winning actress.

And on and on and on. You get the idea. It’s not that any one of these individual instances is all that egregious (okay, a few are). It’s more that the pattern in aggregate is a bit overwhelming. Not to mention dispiriting.

Spend a few minutes Googling around and you quickly realize that most big name brand screenwriters and showrunners and directors just happen to come from quite affluent, well-connected families. Often, incredibly affluent, incredibly well-connected families.

Side note: I sure do wonder why so many Hollywood stories often feel out of touch with the lives of everyday working people.

Anyway, my parents were the day and night janitors of my small town elementary school.

And no, I'm not as successful as the writers and directors I just listed. And yet, here I am, about fifteen years into a screenwriting career, doing alright and working steadily.

I'm certainly not the only working writer in Hollywood with a blue collar background. In our Poker Face season two writer’s room, we even had another writer whose father was an elementary school custodian like my parents were, plus another writer whose mother was the school lunch lady.

That said, I’m also guessing we were the only writers room in Hollywood in 2024 with three children of public school employees in it. The truly blue collar screenwriter is a bit of a rarity in the industry these days, increasingly so.

But let’s assume you’re an aspiring screenwriter from a modest background who wants to do this for a living anyway. How in the hell do you go about competing with the legions of born-to-it insiders?

One way is by offering the industry something that those insiders can’t offer.

For me, it’s been this:

I’m a trailer park blue collar guy from small town America who went on to get an MFA in poetry and a Ph.D. in American literature.

I also happen to think I’m a really good writer and director. As it turns out, there are plenty of other people around town who can claim the same. But as far as I know, there’s no one who can claim my particular biographical profile.

So I’ve tried to turn that to my advantage. From the beginning of my career, I’ve presented myself to the industry as a screenwriter who can authentically tell muscular blue collar stories, hopefully with a bit more lyrical panache than expected.

I’ve very rarely stepped outside of this chosen storytelling lane. When I go up for hired gun type jobs — like say showrunning the second season of Poker Face — I usually go after jobs that are either directly in this lane, or that are at least adjacent to it.

When I generate my own original shit, it’s usually shit that fits into this lane as well.

It helps that I’m genuinely most deeply drawn to this kind of material anyway. But I’m a pretty practical guy. So I happen to believe that this is also the rare lane that the fancy prep school Ivy League nepotism types who dominate the industry can’t really compete with me on.

I’ve very purposefully built an industry-facing persona for myself. It helps, of course, that this persona is based on who I actually am. That said, I definitely emphasize my blue collar roots and small town sensibility — in meetings, in my scripts, on this substack — mostly because I think it helps my chances in getting paid to write the kinds of blue collar muscular scripts I want to get paid to write.

It’s leveraging my outsider status to help extend my career in an insider-driven industry.

When you’re breaking in, I think your number one goal shouldn’t be to sell a script. Or to get a good score in a contest. Or to impress your friends.

I think your number one goal should be to get into rooms.

That means getting into rooms with agents and managers and executives. And producers and directors. And actors and actresses. Getting into rooms, into zooms, onto phone calls, onto text exchanges. Your career won't really start until this happens.

A career isn’t made on a single sale. Besides, original specs don’t get bought up all that much anymore.

But a really strong script can lead to a bunch of meetings, which can lead to relationships, which can lead to opportunities, which can lead to a series of situations wherein you are offered some amount of money to write a script for someone else.

Which is also called a screenwriting career.

A script can get you a meeting. But for that meeting to turn into a payday, I suspect you’ll need to offer something beyond just professional level screenwriting skills. There are already a shit ton of writers in L.A. — many with better connections than you and I will ever have — who have professional level skills. Or who are at least close enough to it.

So, you need something else. For some writers, that “something” is a dynamic personality. I’m a fairly quiet dude who just wants to write cool shit, make cool shit, get paid for it, and spend the rest of my time with my family.

So, dynamic personality: certainly not me. Perhaps it’s not you as well. If so, here’s a way of thinking about what that “something” could be, especially if you’re a bit of an outsider:

What about your life sets you apart from the typical Hollywood screenwriter?

What genre of scripts would you most want to get paid to write over and over again?

How can you connect the answer to #1 to the answer to #2 so they reinforce and feed one another?

For me, it goes like this:

My combo of a rural blue collar background and a literary-academic pedigree sets me apart.

I’d most like to write muscular, somewhat macho, somewhat populist genre stories for a living. Crime stories, cowboy stories, sports stories, mystery stories.

I specialize in macho genre stories set in flyover America. I try to write these stories with unexpected depth, off-beat humor, and surprising lyricism.

That’s kind of my career in a nutshell.

Pretty much everything that I’ve written — stuff that got made, stuff that got me paid, or stuff that I have currently in development — is a somewhat macho genre story set in America, usually dealing with class and/or rural life in some way.

It could be a neo-Western crime show set on the border of the Muckleshoot Indian Reservation in Washington state (Tangle Eye, my breaking-in script). Or a neo-Western crime mystery show set on the border of a Cheyenne Indian Reservation in Wyoming (Longmire, my first staffing job). Or a crime show about a blue collar fixer set in Dallas (unfilmed pilot).

It could be a neo-Western crime show set in Iowa in the 1930s (Damnation). Or a crime show set at a Texas honky tonk (TV pilot in development). Or a crime show set at a Missouri truck stop (unfilmed pilot). Or a blue collar underdog sports movie set in the 1980s (The Olympian — not yet produced). Or a blue collar underdog sports movie set in the world of bare knuckle boxing (unproduced film script).

It could be a neo-Western ensemble crime film set in modern day South Dakota (Americana). Or a murder mystery TV show set in early ‘70s Arizona (TV pilot currently in development). Or a crime show set in rural Indiana that’s adapted from a classic movie (TV pilot in development). Or an adaptation of a Korean revenge film set in the world of Dallas megachurches and beauty pageants (unproduced feature script). Or a TV drama set in the world of West Virginia coal mining (unfilmed pilot).

It could be a murder-of-the-week mystery show set all across forgotten pockets of America (Poker Face). Or a class-based home invasion thriller movie set in Alabama (current directing project).

You get the idea. In my career so far, there have been just a couple of exceptions to this lane I chose for myself.

I did a season of TV on The Terror: Infamy that was a horror story (more lyrical-historical than pulpy-muscular). And I did some uncredited rewrites on a studio action franchise film (very pulpy-muscular, but largely set overseas).

But otherwise, I’ve stayed in pretty much the same blue collar Americana lane for 15 years. And even those deviations listed above aren’t that far off my established path.

So, I keep coming back to the same kinds of stories. Partially because I really dig writing these types of stories and like to think I’m good at writing them.

But I keep coming back to them also because I know I can get paid to write them.

Now, I do have some desire of to break into other genres. I have a couple of horror movie ideas and a whole bunch of romantic comedy ideas. And even a slightly sci fi big studio action movie idea.

But even these ideas are all set in blue collar flyover America type of settings. That’s where my interests and sensibilities reside. But that’s also where my paychecks tend to reside, as well.

The name of this substack is Practical Screenwriting for a reason. You’ll have to go elsewhere for idealistic screenwriting thoughts.

I’ve still never sold the script that broke me into the industry, a pilot for a rural crime show called Tangle Eye. Which was a disappointment at the time.

All that script did was get me representation and then get me into meetings. But I now realize getting repped and getting those two dozen or so industry meetings at the start of my career was much more of a blessing than any sale could’ve been.

Those first industry meetings also gave me an epiphany. After my agents passed around my Tangle Eye pilot and talked me up a bit, I flew down to LA from Seattle for a week and a half. Here I was suddenly in Hollywood, meeting all of these fairly fancy and generally very nice people in these expensive LA rooms.

These industry people seemed to like my Tangle Eye script well-enough. It was pulpy, had some good characters, and offered a fairly distinctive voice and point of view and story setting. All good.

But what these industry people really wanted to talk about was my personal story.

Pretty quickly, I learned that my personal narrative — my journey from a small town trailer park kid to a pickle factory worker to an award-winning poet with a Ph.D. in English to now an aspiring screenwriter — made me kind of a unicorn in their eyes.

The very thing that had kept me out of these rooms — my rural, working class background and blue collar instincts— was what made me interesting once I got into those rooms. And that’s when the lightbulb went off.

I can use this.

Even in that first week of meetings, I quickly began shaping the true materials of my life’s story to create a mini-myth around myself. A few key biographical points became the cornerstones: I was born to a teenage single mother in the Ozarks, I had an absentee biological father whom I was told was in prison, I was raised in a series of trailer parks, I started working at a pickle factory job after high school, I took a stray community college creative writing class that awoke the sleeping artist in me.

I also quickly surmised that this mini-myth wouldn’t really help position me for say sci fi or horror or aspirational prestige type of stories, but it would help position me for say fairly-grounded crime type stories.

Luckily, those were the stories I wanted to tell anyway. After I got hired to write for Longmire, the EPs pretty explicitly told me that my biography — I grew up in a similar setting as the TV show — was the deciding factor that got me the gig. They wanted at least one writer in the room who grew up in the show’s environment.

My biography wouldn’t help me keep my Longmire gig, or get me promoted up the chain. I had to do that for myself. But it did help get my foot in the door.

From early on, the combination of my blue collar background and my Tangle Eye pilot script suggested to the industry that I had a definable brand.

Blue collar poet, maybe. Or thoughtful white trash.

Practically speaking, this meant if executives or producers ended up liking me or my writing, I was now someone they could reach out to if they had a blue collar novel or article they wanted to adapt, or a gritty crime show they needed to staff.

I had a niche. And if they ended up with material in that niche, I was potentially on their list. Invaluable.

For some, this probably sounds incredibly limiting. My background and my sensibility was positioning me for just a sliver of the writing gigs out there. Semi-consciously, I knew I had to make a choice early on. I could either lean into my ready-made blue collar macho niche and become a kind of specialist, or I could try to become more of a generalist, more well-rounded perhaps.

I went the blue collar macho specialist route. And I’m very, very happy that I did.

Chances are, no matter how strong your break-in script is, you'll probably never sell it. (I still haven’t sold mine.) Let alone have it produced.

But a great initial script can get you into rooms with people who will end up paying you to do the stuff they actually want you to do: adapt some intellectual property that they control. Staff some TV show. Rewrite some script.

Fairly ruthlessly, I’ve used my personal biography to position myself for jobs in my specialist field. If I’m pitching a take on some property, I’ll often draw upon some element of my biography. And I’ll make certain to flag this to whomever I’m pitching to.

I mean, why not? If a Harvard graduate is pitching a take on a story set in Harvard, they aren’t going to keep it a secret that they went to school there. They’ll probably set scenes in whatever clubs or house they belonged to so they can write the scenes more authentically.

Same logic here. If it works for the story, I’ll often give characters the exact same manual labor (janitor, condo cleaner, factory worker) or customer service (fast food, restaurant, coffee shop) jobs that I used to work. And I’ll talk about that after the pitch. The not-so-subtle message being: I have insight in these worlds that most people in this industry lack. Which I happen to think is still true.

That said, self-positioning shit like this can only get you so far. It can only really help make you seem like the inevitable choice to hire if the other creative elements also line up well. But it can help.

The well-connected shamelessly use their connections to get into these Hollywood rooms. That’s fine. I’d do the same if I was in their shoes.

Insider vs outsider is not really a matter of politics or morality to me. It’s a matter of finding a competitive edge in a cutthroat industry. So I’ll definitely — with subtlety and tact, hopefully — unless subtlety or tact don’t work, then I’ll be more blatant — use my genuinely blue collar biography whenever I can in order to help my chances.

Luckily, I also happen to believe I can also deliver the goods once I do get a gig. A catchy self-myth isn’t a substitute for good writing. It’s just one way I’ve learned to position myself so my writing can — eventually — speak for itself.

What can you practically do about this stuff?

If you’re an outsider, when you're choosing your story for your "breaking in" script, maybe think about how your script might connect with whatever biographical elements are making you an outsider.

This can take many forms. I'm not saying that if you're a black woman working in a Walmart in Oklahoma that you have to write a script about being a black woman working in a Walmart in Oklahoma. Not at all. I'm just saying: think long and hard about what is keeping you out of these Hollywood rooms. Then think about how you might creatively harness whatever that is.

Simply because, if you can get into these rooms (a big “if” of course), your different-ness, your outsider-ness — that’s what's going to set you apart from the privileged insiders who dominate this field. It’s what will capture industry peoples' attention.

Maybe your outsider-status comes through more in your voice, or your humor, or your lead character’s job, or where you choose to set the story. There’s a million creative ways of harnessing your biography to position yourself in this industry.

Whatever makes you an outsider now could make you a more unique, more hireable insider later.

Because unfortunately, if you're not rich and you don't have connections, just being good enough probably won't be good enough. The children of privilege will always have all the connections, money, and time that the rest of us don’t.

So you'll need something different. Something that the privileged can’t offer, yes. But also something that the industry people in these rooms can grasp and use going forward.

Call it uniqueness. Call it authenticity.

But if you have it, milk it. Milk it like a nepo baby milks daddy or mommy’s industry connections.

A unique biography won’t make up for bad writing. But a unique biography can help good writing get more widely read. It can help get you into a room for a meeting, especially if that biography and a strong sample script have some synergy going for them.

Bad news: the industry seems to be contracting. Good news: the industry still needs emerging writers for adapting properties, or for staffing a show.

The industry always wants emerging writers because it always needs fresh voices. Also, it always needs cheap voices — largely because cheap new voices eventually become pretty expensive established voices if they’re any good.

Can you combine your biography with a script in such a way that it will convince an industry person that you are the cheap new voice they need to hire? What will set you apart from the thousands of other people jostling for the position?

Let’s say there’s a certain type of script you’d like to be writing professionally. Romantic comedies, maybe. Obviously you probably should have a romantic comedy sample script to demonstrate your abilities.

But even better would be a romantic comedy script that demonstrates your abilities while also harnessing some element of your unique biography. The script and your biography can combine into a sort of package story that can grab an executive or agent or producer’s attention.

There’s probably lots of screenwriting paths where this makes less sense. I’m not a “big concept” type of screenwriter. So maybe this isn’t as applicable for that type of path. Maybe it’s also less applicable for say hard comedy or horror or action, where it’s more about just delivering the genre goods.

But I will say this. Whenever I’ve found myself in a hiring position for a writer’s room, I always encounter quite a few successful working writers whose sample script is a TV pilot loosely based on their life experience. Some are based on their old neighborhoods, others on former jobs, others on past events or family sagas.

I also pretty much always find myself looking forward to reading these scripts, especially if their agent emphasizes the unique experiences or perspectives informing this script. The combo of unique life experiences and a compelling script based on those experiences makes these writers stand out from the pack.

Years later, I now realize that my initial Tangle Eye script was never really under consideration for being bought, let alone getting made, at the start of my career. It was just the pretext for me getting to meet a bunch of industry people. It actually functioned more like an introductory letter than as a blueprint for something to be filmed.

What that initial script did was give industry people in industry rooms a sense of what I could do for them in the near future. Because that's what 90% of the people I met were really interested in.

They weren’t interested in Tangle Eye as a property, but they were interested in figuring out if the guy who wrote Tangle Eye could apply a similar skillset and point-of-view and perhaps harness the same life experiences while writing something new for them.

If you have an interesting biography or life experience — and if it can inspire a compelling sample script — that might actually be the thing that will grab some industry person’s attention. Especially if your competition is all doing pastiches and imitations of their favorite movies while flouting the same education credentials and connections as everyone else.

You might stand out as unexpected. As refreshing. As authentic.

I wrote Tangle Eye as a modern day revenge Western set where I grew up: a small, predominantly white town bordering an Indian Reservation.

My first industry job was writing for a modern day TV western that was set in a small, predominantly white town bordering an Indian Reservation.

Probably not coincidental. There was a lot of luck involved in my breaking in. But perhaps leaning into the elements that made me different — my outsider background and my taste for old school macho genre stories — prepared the ground for good luck to visit.

Maybe your own version of this could work for you.

Instead of trying to replicate the sensibility of a Hollywood insider, why not offer the industry something an insider by definition can't offer by leaning into whatever makes you different?

Hollywood insiders are relentlessly leveraging their insider status. Why not leverage your outsider status in return?

Tangle Eye was fantastic, grounded in a way that reminded me of the people I knew. 100% agree with you on this article as always. Thanks for caring about writers enough to point the way. You’re a fantastic character writer. The kid from Americana is so relatable.

Always love your insights, Tony. They've definitely helped me in my writing. I guess I always try to apply my background in bigger concept movies that aren't about where I grew up - a desert town in the southwest. Maybe I should try something closer to home?