The Shape & The Juice: Two Ways of Thinking About a Scene

I’m pretty sure the first post I ever published on this poor neglected substack was my personal running list of Screenwriting Principles. I started compiling this list almost 15 years ago, early into my first screenwriting gig writing on the Western mystery show Longmire.

The list started off as a purely personal resource, just a way for me to keep track of some of the practical shit I was quickly learning while on the job. No grand theories of screenwriting were at play, just fairly tangible things I was picking up on, mostly by doing them wrong.

A week and a half ago, we finished filming the second season of Poker Face. I was showrunner for this season, which turned out to be quite the gig, the details of which I’ll save for my memoirs. Right now I’m enjoying the holidays in Arkansas with my family, then I’ve got a few months of post-production ahead of me back in LA, a different, much tamer beast than the production phase. And I guess the real headline is, all in all, I’m absolutely thrilled with what we made and I can’t wait for people to see it.

But right now, I find myself in a reflective mood, on multiple fronts. Coming out of the Poker Face season two experience, I find myself thinking about a screenwriting principle of mine that I don’t think I buy into anymore:

Every scene is about one thing. A scene about two equal things will come across as a scene about nothing. Other shit can happen in a scene, but it has to have one dramatic goal and drive.

Even though I don’t exactly buy into this principle anymore, I came to it honestly. In early drafts of my Longmire scripts, I’d often try to kill two birds with one scene, dramatically-speaking.

Let’s say I had a scene where Sheriff Longmire was, say, upset about something his daughter had done and was now confronting her about it. A good, simple, direct dramatic scene.

But often in my first drafts, I’d find myself thinking: hey, wouldn’t it be great if Sheriff Longmire also got some key clue about the episode’s murder mystery at the same time? Two birds with one scene!

And so I’d engineer a scene, aiming to accomplish both dramatic goals: relationship drama moment and a mystery storytelling beat. And over and over again, I’d finally find out — usually via showrunner Greer Shephard’s gentle illumination — that the scene was accomplishing neither goal.

Having two different dramatic goals in one scene is still a mistake in my book. But I no longer think a scene should only do one thing. Or maybe more exactly, I now realize that “thing” is a hopelessly vague screenwriting term. So I’m revising the principle, in the hopes of getting more practical about how I think scenes work.

So, let me try this as a new principle:

For a scene to work, you need to know what’s giving that scene its shape and what’s giving that scene its juice. A scene without a real shape risks becoming meandering and poorly paced and, worse of all, boring. A scene without real juice risks becoming thin and predictable and, worse of all, boring.

This isn’t anything mindblowing. But I personally find “shape” and “juice” to be strangely useful terms.

I’m enough of a traditionalist to think that scenes should have a dramatic shape. A reason to start, a reason to end, and a reason to bridge the gap. I like scenes that move, and that move the story forward. But I don’t tend to like scenes that only move, and that only move the story forward. I also like scenes to have some juice (I know it when I see it.)

Let me use an example from a terrific film full of terrifically juicy scenes: Fargo.

Specifically, the scene where Marge Gunderson arrives to investigate a bewildering snowy situation: an overturned car with one dead body inside and another dead body nearby, both dead from gunshot wounds. Plus a dead state trooper and his patrol car in the nearby vicinity.

So, what gives the scene its shape? That’s easy. It’s a pretty pure procedural scene. Marge shows up and gets the basic facts from another cop. Then we join along as she takes in the terrible situation, one observation and deduction at a time.

Dramatically, the shape is clear. Marge goes from perplexity to observant curiosity to deductive realization. It’s a shape you might see in any weekly procedural show. Sturdy as hell, but nothing innovative or showy or particularly clever.

So what gives the scene its juice? That’s also fairly easy (to observe at least, if not to pull off). I think the juice in this scene derives from us realizing that this pleasant, unassuming, very pregnant woman with a funny way of talking is in fact one hell of a good detective.

The shape is fairly well-worn genre material. You’ll find it in hundreds of other crime and mystery type films and TV shows. But the juice is unique to this movie itself, and particularly to this character.

If Marge Gunderson was conceived as a gruff divorced cop named Doug Gunderson who has a drinking problem and a hard-boiled manner of speaking, you could drop him into this exact same scene and give it the exact same shape.

The scene would work, structurally and dramatically. But that’s all it would do. The scene suddenly wouldn’t have any juice.

Yeah, no shit right? Great insight. Good scenes need good characters. Duh.

But if it’s all so obvious, why do so few scripts work as well as Fargo does?

Here’s another scene from the movie that has a familiar shape but distinctive juice.

It’s the opening scene. Jerry shows up at a bar to make a deal with a couple of hoods. He’ll give them money and a car if they’ll kidnap his wife.

Again, the shape here is very basic. It’s a negotiation. Jerry comes to them with a proposition, they haggle a bit, and then they come to an agreement. Incredibly simple.

So where does the juice come from? It doesn’t come from the negotiating tactics or strategies at play. Or even from the stakes.

The juice comes from the sheer incompetency and pettiness of the three men involved. Jerry is a timid weaselly fucker. The hoods are anti-social idiots.

You could tell this same story, plot-wise, with more capable, socially-agreeable characters. Jerry could be confident and punctual. He could offer the same proposition. The hoods could be socially-competent.

The trio could ultimately agree to the same deal. And the same crime plot and disagreements could unfold from this agreement. Again it would function well-enough, but it wouldn’t have any juice.

In both the Marge scene and the Jerry scene, I’d argue that the juice — the thing that makes the scenes interesting and memorable — doesn’t come from the dramatic situations involved. We’ve seen good cops make good deductions before. And we’ve seen bad husbands and bad criminals make dastardly plans before.

The juice in these scenes comes from this: both Marge and Jerry seem to be incredibly ill-suited for the situations they find themselves in. Marge is seemingly too friendly and too happily domesticated to be such a fantastic cop. And Jerry is seemingly too meek and chickenshit to concoct such a nefarious criminal scheme, or to pull it off.

Now, not every scene can rely on this same dynamic. It’d get old very quick if every single scene featured a character ill-suited for a fairly standard genre situation.

But these are essentially the introductory scenes for Marge and Jerry, where we get to know who they are and how they think. We get introduced to a pleasingly familiar small town crime scenario while also being introduced to characters who — because they don’t seem well-suited for that genre scenario — suddenly make that familiar scenario funny, rich, and unpredictable.

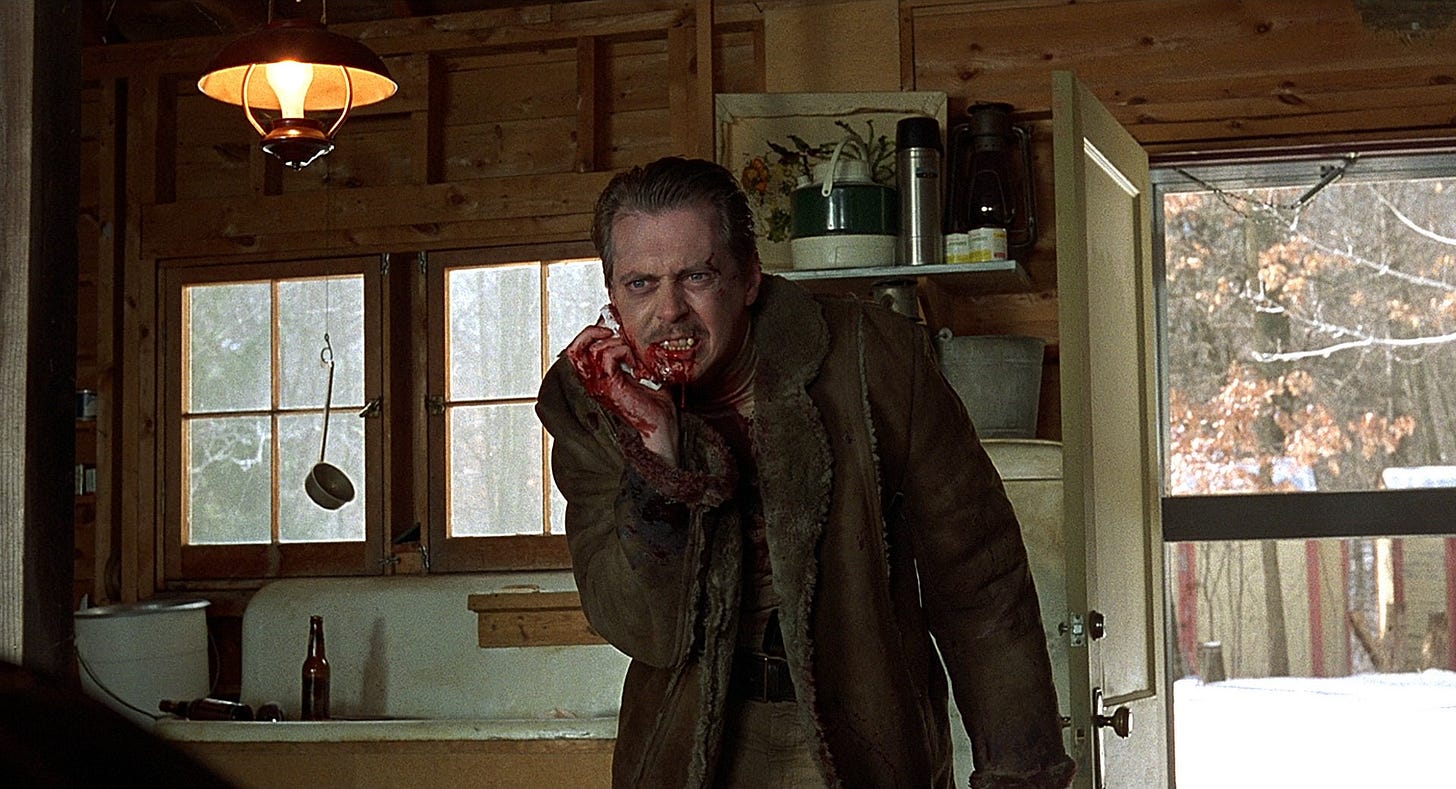

Another scene I love is when Steve Buscemi’s character returns to the cabin after getting shot in the face. He’s secretly gotten a huge windfall and really should just do whatever it takes to get away from his partner. But because he’s an angry idiot and his partner played by Peter Stormare is a psychotic idiot, Buscemi ends up getting axed in the head instead.

Like the opening scene with Jerry, this scene is a negotiation. It should be simple. All these two idiots need to do is come to terms. The juice comes from the fact that — as established in that opening scene — they’re both too anti-social and idiotic to manage such a simple transaction. Their lives and a fortune are on the line, but they can’t get past their very petty grievances. The juice comes from the bigness of the situation meeting the smallness of their humanity.

One last key scene is when Marge tracks down Stormare’s character and goes to arrest him. The shape once again is basic: a confrontation between our hero and our villain. Either she’ll arrest him, or kill him, or she’ll be killed.

This is a dramatically charged scene: a lovable, pregnant, capable-but-vulnerable woman is going to confront a psychotic physically-imposing murderous man.

But if you bring up this scene to anyone who has seen the movie, they won’t refer to this as the climactic scene, or the showdown scene, or the arrest scene. They won’t discuss the dramatic charge of a life-or-death situation.

No, this is the woodchipper scene.

What makes this scene unforgettable — what gives it all-time level juice — is simply the bizarre, gruesome detail that Stormare happens to be in the middle of disposing of Buscemi’s body by using a woodchipper at the moment when Marge spots him.

That’s it. The image is the juice. The Coens could’ve staged a traditional action setpiece here, where Marge and Stormare end up out on the frozen lake in a shootout, or in the snowy woods, or any other action situation we’ve seen before.

But wildly, brilliantly enough, they don’t try to squeeze too much juice from the drama, or the danger. Stormare actually ends up getting taken down pretty easily.

Instead, they get their juice by presenting us an image that’s both wildly unexpected and also perfectly suited for this particular milieu. It’s hilarious and terrifying and, in my opinion, truly genius stuff. It’s a level of artistic showmanship that’s beyond any kind of principle or piece of advice. It’s just inspired.

So anyway, shape and juice. Weirdly useful terms for me, especially early in the writing process. Perhaps they can be of some use to others as well.

Here’s a random theory: maybe one reason why so few big ticket event type of stories seem to work as well as they’re intended to is because they’re all trying to squeeze their juice from over-squeezed sources. Big plot twists. Big spectacle. End of the world stakes. Big stars winking at the camera while flexing.

But juice, real juice — the really memorable, interesting, entertaining, woodchipper type shit — isn’t a one-size-fits-all type of deal. You can’t take tried-and-true characters and stick them in tried-and-true situations and then expect it to somehow be entertaining just by turning the violence or the spectacle or the snark up to eleven.

Juice — as far as I can tell — can’t be pre-engineered. It has to be found and cultivated and won, scene by scene. It’s an open question as to what degree modern Hollywood practices of project development and brand maintenance will even allow for real juice-cultivation to still happen. And yet, it’s our job to make it happen anyway.

Glad to see you back

Top-tier post, Tony. Glad the season went well - good to have your thoughts here again. Thanks.