"Our Job Is to Make Entertainment"

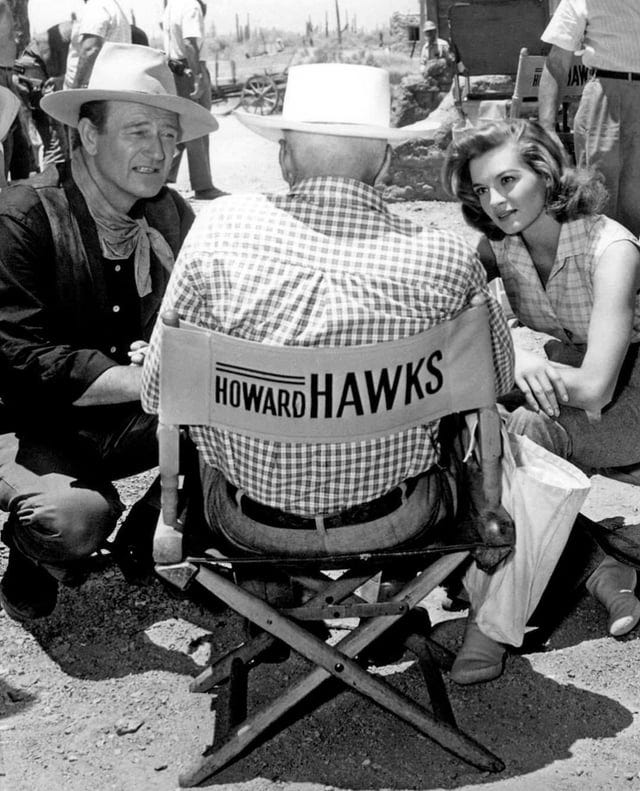

directing & screenwriting tips from my all-time filmmaking hero, Howard Hawks

In the Poker Face writers room, one of the writers came up to me.

“Hey, want to see my Tony Tost impersonation?” she asked.

“Sure,” I answered.

“Howard Hawks, Howard Hawks, Howard Hawks,” she said.

It was a pretty accurate impersonation.

When I tell people in the industry that I’m basically just trying to be a modern day Howard Hawks, I’m usually met with blank stares. Oh well.

What I mean is this: I want to tell audience-friendly stories in popular genres with memorable characters and great scenes. Within that self-selected sandbox, I also want to work through my own pet interests and obsessions, but without any real politicking or self-serious grandstanding.

Now, I don’t think the Hawks approach is the only valid approach to cinematic storytelling. It’d be really boring if everyone told stories the same way.

Hawks just happens to embody the ideal approach for the types of movies and TV shows that I want to make.

Only Angels Have Wings is one of my three favorite movies of all-time. Rio Bravo and Red River are in my all-time top ten. His Girl Friday, To Have and Have Not, The Big Sleep, Ball of Fire, Scarface, and El Dorado are way, way up there too. He’s got another dozen or two movies that are more than worthwhile as well, ranging from the silent comedy A Girl in Every Port to the African safari hangout adventures in Hatari to the musical comedy of Gentlemen Prefer Blondes.

As it turns out, my idea of a relaxing weekend is scouring through my Howard Hawks books to search for directing and screenwriting advice from the maestro. I started collecting these nuggets into a document. I figured I may as well share them here, as well.

Most of these quotes are presented verbatim. A few have been slightly tweaked for clarity and brevity after being taken out of context of a longer conversation.

I think our job is to make entertainment.

The average movie talks too much. You have to plant your scenes and then let the audience do a little work so they become part of it.

When you leave the dialogue out and make visual stuff, the visual stuff has so much more impact because you hadn’t used it before.

Your job is to do the scene a little differently. To get mad a little differently. To steal a little differently.

I try to tell my story as simple as possible, with the camera at eye level.

You’re not trying to photograph a budget or a cost sheet. You’re trying to make a scene that’s going to be good. I think all the good directors are loose. None of them made a scene until they thought it was any good.

I’m interested first in the action and next in the words they speak. If I can’t make the action good, I don’t use the words. I must change the words to fit the action because, after all, it’s a motion picture.

If you see the pictures that I make, you’ll find a certain similarity in the dialogue and the fact that it’s short and quick and rather hard.

One thing you can do is look at all the pictures I’ve ever made, and you’ll see that nobody pats another person on the back. That’s the goddamnedest inane thing I’ve ever known.

While working on a script, my writer would read one character, and I would read another character. We’d read our lines of dialogue, and the whole idea was to try and stump the other, to see if I could think of something crazier than you could.

As long as you make good scenes you have a good picture—it doesn’t matter if it isn’t much of a story.

Once you get on a solid base, you can be funny without having a comedy plot. Generally, we start seriously just to interest people and see that the story gets going. Then you can start having fun with the characters. So the comedy creeps up on people—they aren’t told to laugh. And the more dangerous, the more exciting, the easier it is to get a laugh.

If people start a picture and they have a funny main title, a lot of funny things, it’s as much as to say, “We expect you to laugh.” I think that’s committing suicide. The audience is going to go against it.

True drama is awfully close to being comedy. The greatest drama in the world is really funny. A man who loses his pants out in front of a thousand people—he’s suffering the torture of the damned, but he’s awfully funny doing it.

All I’m doing is telling a story. I don’t analyze or do a lot of thinking about it. I work on the fact that if I like somebody and think they’re attractive, I can make them attractive. If I think a thing’s funny, then people laugh at it. If I think a thing’s dramatic, the audience does.

I don’t believe in people trying to be funny.

A comedy is virtually the same as an adventure story. The difference is in the situation – dangerous in an adventure story, embarrassing in a comedy. But in both we observe our fellow beings in unusual situations. You merely emphasize the dramatic or the comical aspects of the hero’s reactions.

I’ve seen so many people laugh at violence when it happens. Kind of hysterical laughter. It’s the easiest time for you to get a laugh.

A comedy can really be ruined by being shortened. If you take out the scene which is planted to make the following scene funny, then the following scene is not funny. The movie suddenly becomes slow.

If a scene is a bit weak, the more rapidly you shoot it, the better it will be on the screen.

I can’t remember ever using a funny line in a picture. The characters become funny because of their attitudes, because of the attitudes that work against what they’re trying to say.

Whenever I hear a story, my first thought is how to make it into a comedy, and I think of how to make it into a drama only as a last resort.

Dialogue comes easy if the attitudes are right. You’re just playing with something in order to get away from the usual thing.

Hemingway calls it oblique dialogue. I call it three-cushion. Because you hit it over here and over here and go over here to get the meaning. You don’t state it right out. I believe that this particular method makes the audience do the work rather than coming out and making a kind of stupid scene out of it.

If a girl is gonna say how broke she is, you’ve got to find an awful good metaphor to use. Something that happened, that’s how broke she is. You draw a picture of it.

I think it’s kind of boring to lead you into all of the details right away, because then you know what’s going to happen and the scene where it comes off is no good. But a movie can start with a perfectly good scene and then go back later and explain the story.

Very often I just let the so-called climax go by pretty quickly. I know what the audience expects and they’re sitting there expecting it and they feel a lot better if you just get over it.

If I’d think of something, I’d go to the actor and say “Don’t tell this other guy about it, but read such-and-such a line” He throws the line to the other actor, and the other actor at first doesn’t know what to say, and then he responds in his own way, and it always works out well.

You don’t have to do a lot of rehearsing with any good actor. You merely tell them what you’re trying to get out of a scene, then you just turn them loose and let them go.

Instead of saying “Action!” which I think is a silly way to start a scene, I say “Camera.”

The dumbest thing in the world is an actor getting serious about himself. For God’s sake, don’t get so serious about it.

I think that when actors get to mumbling over lines so long, they get very bad, but if they just come out with it, they usually say the right thing.

God knows what an actor needs. You have to find out what he needs and do it.

I had noticed that when people talk, they talk over one another, especially people who talk fast or who are arguing or describing something. So we wrote the dialogue in His Girl Friday in a way that made the beginnings and ends of the sentences unnecessary; they were there for overlapping.

I want the actors to speak over the lines. I want the sound man to tell me whether or not he can understand the dialogue. If he can understand it, that’s fine.

I have insisted on previewing comedies, but I haven’t cared about whether we previewed dramatic pictures. But with a comedy, you’re crazy if you don’t, because just little changes in cutting can make a thing funny or bad, or a laugh can carry over and spoil something that’s coming.

I work at about twenty percent faster speed than the average picture. When an actor does a scene, I say, “Do it in twenty seconds less and it’ll be pretty good.” And if they don’t do it in twenty seconds less, then I cut their dialogue down to practically nothing and tell them to go ahead with it. Because it’s just as good a scene, and it gets it over in a hurry.

I’m always fighting against scenes that might annoy the audience. I told John Wayne on Red River: “Look, don’t try so hard on every scene. If it’s a real good scene go to work on it and work hard, but if not, get it over in a hurry and don’t annoy the audience, because if you do two good scenes in this picture and don’t annoy the audience the rest of the time, you’ll be good. If I make four good scenes, I’ll make a good picture—if I don’t annoy the audience the rest of the time.”

If you try to keep up high all the time, you’re just gonna tire them out. And you’re gonna annoy them, because nobody is capable of writing in such a fashion that you can keep emotion at a high pitch all the time.

It’s awfully hard to get anybody today who can write funny. They try to write dialogue that’s funny, and no, I don’t trust dialogue at all. But I can write action that’s funny.

In Rio Lobo, we have a girl call John Wayne “comfortable” and “old” and everything. I kid every actor, if there’s something that I can kid him about—put it in the dialogue.

All these TV actors hear these laugh tracks and they begin to think they’re funny and that they’re cute. Just messes them all up. They get the cutes.

I don’t like close-ups unless you can get a kick out of them, unless you need them. If you can get away with attitudes and positions that show the feeling of the scene, I think you’re better off using the close-up only for absolute punctuation.

It’s also better to save those big close-ups until the audience begins to know a little about the people, and then that person’s face and what he’s thinking means more to them.

If I had something I liked very much that I thought somebody was going to fuss with, I didn’t cover myself. If it came to a scene I didn’t like too much and was perfectly willing to cut down, I made a lot of protections.

Any script that reads well is no good. If it starts out with, “He looks at her and the yearning of ten years shows in his eyes,” you’re in trouble. I’ve never found an actor who can do that.

I’ve never made a picture to be anti- anything or pro- anything.

The plot doesn’t matter at all. All we are trying to do is make every scene entertain.

If you can do characters, you can forget about plot. You just have the characters tell the story for you, and don’t worry about the plot. I don’t. Movements come from characterization.

The difficult work is the preparation: finding the story, deciding how to tell it, what to show and what not to show.

I'd say that everybody has seen every plot 20 times. What they haven't seen is characters and their relation to one another.

We just keep fussing with a scene until it begins to look good, that’s all. We get strange things sometimes.

You may have a perfectly good scene, but as the character becomes clearer to you, you realize the scene you are doing has little or no characterization, so you begin to add character to the man. You’re actually doing the same scene, but you’re giving him a few different words and you’re getting a few different attitudes into it.

I think most of the guys tried to be so tough in gangster movies, they were always doing everything in a heavy-handed way. We did Scarface differently. We did ours in a kind of joking way. We saved the animosity for the personal scenes. The other stuff was done without any show of feeling. I objected to what was done in so many pictures—that overemphasis on trying to be tough. Even in the middle of some of the roughest stuff, there was a kind of seriocomic approach.

Almost all the men in my pictures have gone through some troubles. Then they have to be straightened out. That makes interesting writing.

Practically everything is rewritten after someone is cast. I never try to make people play something they aren’t. It’s much easier to write for the best things they do and let them play those things. It doesn’t take long.

If I got an actor who was particularly good and had a certain quirk or something he did that I liked, I’d rewrite the part for him.

When we began to work on To Have and Have Not, Jules Furthman wrote a scene of Lauren Bacall in a strange port and her purse gets stolen. I read the scene and said, “Well well well, I think its such a sexy thing to present a poor young thing who has just had her purse stolen.” So he said, “OK OK,” and went off and wrote an introduction of a girl who stole a wallet and that became very interesting.

In Rio Lobo, I had a bad actor but such a nice guy I didn’t want to say “You’re lousy,” so I had him hunting for a whiskey bottle all through his scene. All he had to do was just throw the lines at John Wayne—and he played it fine.

If you’re ever stuck and get into a scene you don’t think should be exposed to people—shoot it so they can’t be seen too well. It can cure an awful lot of evils.

John Ford said if he had a scene that he didn’t think was good enough, he’d do it in a long shot rather than try to punch it up. If I’ve got a scene like that I just try to do it as quick as I can.

I decided that audiences were getting tired of plots. But if you can keep them from knowing what the plot is you have a chance of holding their interest. And it leads to characters who motivate your story: it’s because the characters believe a situation happens, not because you write it to happen.

When I find a scene is a little too sentimental, I try to turn it around to keep it from being that way. In Only Angels Have Wings I had a man talking to his friend who’s been in an airplane wreck. He tells him, “Your neck’s broken, kid.” Just a flat statement; just try to keep things from becoming mawkish. Play against it completely.

If you look at my career, you’ll find that I like actors less than I do personalities.

The reason why stars are good, they walk in through a door and they think, “everybody wants to lay me.”

I don’t remember James Cagney ever suggesting a line—it’s the way he does the line that makes him so good. Whenever I work with a fellow who was as good as Cagney—let’s include Bogart there—I made sure they felt free to try anything. We try things one way, we try things another way. Every scene almost, we’d say “How was that?” “Pretty good. It’s a little usual. Can’t you think of some different way of doing it?” And we’d do it. The reactions and things would change the scene a little bit. Not really change it, but it would make an interesting scene.

I firmly believe the camera likes some people and the camera dislikes other people. Somebody that the camera likes has an awful time doing wrong. Somebody that the camera dislikes has not got a chance in the world.

Once you begin shooting you see everything in the best light, develop certain details, and improve the whole. I never follow a script literally and I don’t hesitate to change a script completely if I see a chance to do something interesting. I like to work on the scenarios.

Dramatically it’s great—a guy fights with someone who’s got a tough job to do and then ends up being put in the same position himself. That’s always a hell of a story—you can’t go wrong with it.

If you’re making an airplane picture, you start with an airplane [crash]. If you’re making a war story, somebody gets shot at the beginning. Red Line 7000 started with a horrible crash. You get the audience to realize that they’re dealing with life and death. It’s just that simple.

The best thing to do while directing is to tell a story as though you’re seeing it. Tell it from your eyes. Let the audience see exactly as they would if they were there. Just tell it normally.

Once in a while, I’ll move the camera as if a man were walking and seeing something. And it pulls back or it moves in for emphasis when you don’t want to make a cut. But outside of that, I just use the simplest camera in the world.

Action scenes are much more dramatic if they’re shot at night. You’re able to light the set so the audience sees what you want them to see. You go out in bright sunlight and shoot—-oh, there’s so many things for your eye to follow. It’s just something I’ve always done.

What’s good about flashbacks? If you’re not good enough to tell a story without having flashbacks, why the hell do you try to tell it? I hate them. Just like I hate screwed-up camera angles.

You can make fun of anybody and it amuses people if you don’t get too mean about it.

I discovered that when I’ve liked an actor, the audience liked him. But sometimes they’re pretty hard to find, so you take substitutes.

You can always make fun of other people’s seriousness. The more dignified people are, the easier it is to laugh at them.

If a character that the audience likes in a picture likes somebody else in the story, that’s the best boost for a character that you can make. Now, if you’ve got a heavy liking someone, that’s no boost. But when you’ve got a nice guy that likes someone, immediately that character is boosted.

I tell my cameramen, “If you make two good scenes for me, you can make two mediocre ones and one bad one.” All I’m interested in is the good one. So they go ahead and take chances, and their work shows it.

In the beginning, I was very much impressed by Murnau’s Sunrise, particularly for its camera movements. The other directors who have most impressed me are John Ford, Ernst Lubitsch, and Leo McCarey.

I finally got tired of other people directing and me writing, so I went to see a movie every night for six months. And if I thought the movie was worth studying, I saw it twice that same night until I felt that I knew enough to direct. I learned right in the beginning from John Ford, and I learned what not to do by watching Cecil DeMille.

John Ford was a good director when I started, and I copied him every time I could. It’s just as if you were a writer, you would read Hemingway and Faulkner and John Dos Passos and Willa Cather.

Ford worked beautifully with bad weather. And he doesn’t care whether it matches when he goes into close-ups. He stages a tableau, a long shot, and gets that into your mind, and then cuts in for a close-up and you never notice the difference in the lighting or anything.

Every time I run into a scene that I think Ford does very well, I stop and think, “What would he have done there?” And then I go ahead and do it.

Ford would tell me what things he stole from me, and I’d tell him what things I stole from him, but we did them so differently that it didn’t make any difference whether we stole them.

The western is the simplest form of drama—a gun, death—and they all fall, really, into two kinds. One is the history of the beginning of the West, the story of the pioneers, which was the story of Red River. Then there’s the phase when law and order comes.

I’m much more interested in the story of a friendship between two men than I am about a range war or something like that. There’s probably no stronger emotion than friendship between men.

If you want to make pictures and enjoy making them, you better go out and make something that a lot of people want to see. And then they’ll turn you loose and let you make what you want. And then maybe you can do some of the things that you want to do.

I make movies on subjects that interest me: That could be automobile racing, airplanes, a western or a comedy, but the best drama for me is the one which shows a man in danger. There is no action where there is no danger.

I have no desire to make a picture for my own pleasure. Fortunately, I have found that what I like, most people also like, so I only have to let myself go and do what interests me.

They're moving pictures, let's make 'em move!

I still don’t believe in killing people and making a picture end with death.

What a great post and list.

The most interesting thing for me, (someone who dabbled in my youth (decades ago) with screenwriting (and did write partly dramatized documentary) is the drumbeat emphasis on scenes as the meaningful unit of film making. Not lines or beats or acts or dramatic art. Scenes. None of what a lot of the screenwriting manuals popular when I was reading up on the craft emphasized. (McKee, etc.) I am going to think hard on the implications, not just for film or television, but for what I now make my living writing (non-fiction, mostly history).

This is a great list. Would you also mind sharing some of the books these quotes are sourced from? Or at least the ones you recommend? Thanks for all the great writing!