One For Them, One For Me

one way of thinking practically about a screenwriting career

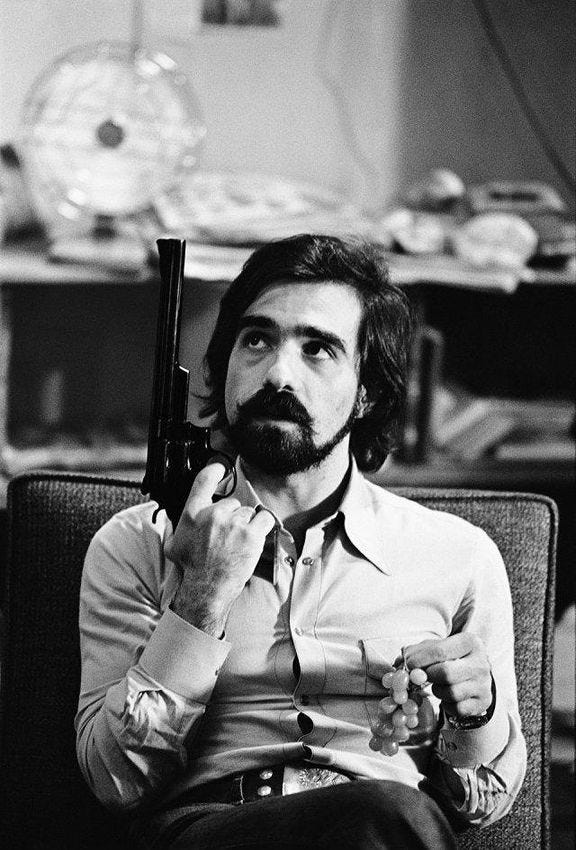

It’s usually attributed to Martin Scorsese, the Hollywood concept of alternating between more commercial projects (“one for them”) and more personal ones (“one for me”). This is often seen as reflective of the compromised nature of being a commercial artist and proof that art-for-art’s-sake just won’t fly when big money capital is necessary to finance that art. And this is probably so.

Famously, Scorsese was only really able to finally get financing for his passion project of The Last Temptation of Christ — which he’d been wanting to make for about a decade — after the commercial success of The Color of Money, which was after all a hired gun sequel to a hit film with an honest-to-God movie star Paul Newman at its center and rising star Tom Cruise as his protege.

By Scorsese’s own account, Newman was very much the driving force behind the picture as the one indispensible element of its package, though of course Scorsese, Cruise, writer Richard Price, cinematographer Michael Balhaus, editor Thelma Schoonmaker, and the wildly underrated Mary Elizabeth Mastrantonio all proved essential to the film’s success.

And after creating this slick Hollywood sequel and getting Newman a long-awaited Oscar, Scorsese was finally in good enough graces to get financing for his more substantial passion project. Perhaps it’s ironic, though: as much as I love the much more literate and profound The Last Temptation of Christ, I happen to love The Color of Money even more.

Great directors making adult popcorn movies is sort of my aesthetic ideal. Which is maybe why “one for them, one for me” has always sorta sounded like a dream to me.

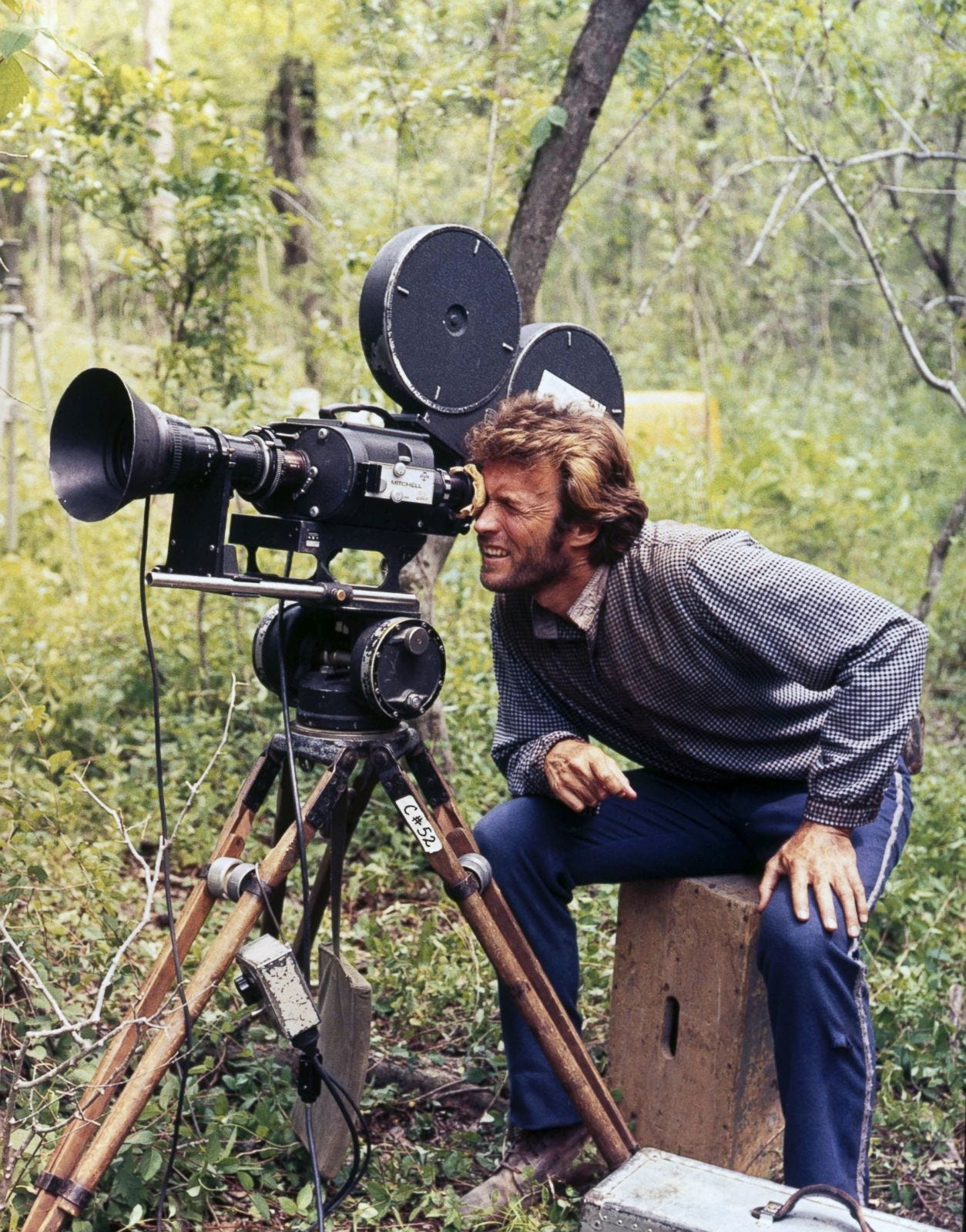

I’ve long heard rumors that Clint Eastwood’s long and insanely mutually-beneficial relationship with Warner Brothers was based on a similar “one for them, one for me” setup, with Mr. Eastwood alternating between films he had total creative control and films that the studio wanted him to make. Apparently, the only reason he was able to get away with casting the real life individuals portrayed in The 15:17 For Paris was because it was one of his creative control movies.

There are a lot of reasons why Mr. Eastwood is among my artistic heroes. Here’s one of them: going through his incredible filmography, I often have a hard time guessing which projects were “one for me” and which were “one for them.”

That is, his personal tastes and interests and the studio’s perception of what a paying audience wanted from a Mr. Eastwood film are so well-integrated that they are often more or less the same thing. I mean, clearly his Charlie Parker biopic Bird was a “one for me,” as were his Dust Bowl dying country singer picture Honkytonk Man (one of my favorite Mr. Eastwood films) and his thinly fictionalized portrait of John Huston White Hunter, Black Heart (another favorite) and his character study of a failing Wild West huckster picture Bronco Billy (not a favorite). But otherwise, it’s pretty hard to tell.

Mr. Eastwood did two of my favorite films of all-time back-to-back: Unforgiven and A Perfect World. If the “one for me, one for them” template is true, I have a hard time differentiating which was which. Was it the absurdly dark revisionist Western that spends most of its time taking the piss out of Mr. Eastwood’s iconic persona? Or was it the perfectly rendered mid-century fable about an outlaw and a boy on the run that starred Kevin Costner, probably the biggest movie star in the world at the time? (Costner’s previous four films were The Bodyguard, JFK, Robin Hood, & Dances With Wolves.)

You can still see remnants of the “one for me, one for them” approach in the present day when you hear rumors that Nolan did The Dark Knight Rises primarily so he could then get financing for Dunkirk. For high profile filmmakers, it strikes me as a very smart way of balancing the pragmatic and artistic demands of a long career.

Now, I’m neither a Scorsese nor a Mr. Eastwood nor a Nolan. But I still think that a “one for me, one for them” approach is applicable even at my more modest career’s scale.

Here’s one way: any time I get hired for a writing job on a project that didn’t generate inside my own brain, I almost always immediately begin writing something new on spec.

I started this practice back when I was a staff writer for the TV show Longmire.

Before trying my hand at screenwriting, I had spent the previous 15 or so years of my writing life as a poet and a critic. As you might expect, poetry and cultural criticism don’t pay for shit, which is why I was also going to be a professor. (I quit my professor job a month after getting it when I first got hired to write on Longmire.)

But there’s also some non-financial compensation for doing writing that pretty much no one else cares about: there’s nothing really stopping you from writing whatever the hell it is you want to write. So on one hand, I was ecstatic to be working in TV and making more money than I ever had in my life, especially as a young-ish father of two kids under the age of four. (Until my first year working as a screenwriter at the age of 35, the most money I had ever made in a year was $23k.) On the other hand, I also had to adjust to not having complete creative control of my writing for the first time in my entire life.

Things were fine on this creative control front for the first year or two. I was too busy just trying not to blow my big chance. I spent six months of each year working on Longmire for the most wonderful showrunner on earth (Greer Shephard), learning my craft from working alongside uniformly rad writers, directors, cast, and crew. And I spent the other half of each year developing pilot scripts for a handful of different studios. One of these pilots was the brainchild of an actor, another was an original idea of my own, another was an adaptation of a series of Scandinavian crime novels, and so on.

But a couple of years into my career, I found myself getting increasingly creatively frustrated. I think this had less to do with Longmire itself — as I mentioned, everyone there was amazing. Plus, I was afforded quite a lot of input on my episodes. I mean, I always had rounds of notes, but they uniformly made my episodes better, and they were a masterclass in learning structure in particular. I was writing 3 to 4 episodes a season, producing most of them, having a lot of fun with a group of great great people, and was very proud of the show.

But it wasn’t my creative vision. And that started to gnaw at me a bit. I think the real source of my simmering creative frustration was what I was doing the other half of each year: developing these multiple pilots with multiple studios and producers, two or three projects at a time, trying to figure out how to address various producer notes when — on one project in particular — oftentimes the producers giving those notes didn’t consult amongst themselves and wanted the show to go a multitude of different ways. (This was before I learned that I ultimately had to trust myself and that it was better to get fired from a project than to try and write something I didn’t believe in.)

My frustration from the pilot development process started bleeding over to my work on Longmire. I found myself quietly resenting having to write in someone else’s voice — even though that was exactly my job, and I was lucky to have it, and this voice was actually the best voice for the show. This silent resentment was starting to negatively influence my work performance in subtle ways.

Thankfully, I started to realize this. And the way I coped was this: I just started writing something for myself on the side, purely as a creative outlet. I now had something that wasn’t answerable to anyone else and that wasn’t even conceived as something to bring to market. It was just a pressure release valve in the form of a TV script. As fate would have it, this creative diversion ended up being the first two episodes of Damnation, the only original TV show I’ve gotten on the air so far.

After first writing these Damnation episodes, it’d still take me several years to finally getting that show actually on the air with me as the showrunner. And I spent these years continuing to work on Longmire, making my way up from freelance writer (first two seasons) to writer-producer (the last couple of seasons). But even if my Damnation scripts had never gotten sold or had never gone into production, they were quickly of great value anyway.

Why? Since I now had this backpocket passion project I could obsess over and work on in my spare time, I suddenly possessed a much better attitude about both my staffing job and my development gigs. In terms of Longmire, I could once again live up to my personal credo: “high performance, low maintenance.”

Because I now had a “one for me” always waiting for me on my laptop, I could take notes on my “ones for them” in a more generous, creative manner again. My Longmire episode scripts no longer were little barometers measuring my personal degree of creative autonomy.

Instead, they could be what they were supposed to be: blueprints for making compelling television within the bounds of my showrunner’s vision, which resulted in a show popular enough to run for six seasons. Likewise, suddenly having to deal with producer or studio notes on these pilots in development didn’t feel like a tortuous hyper-personal tugs-of-war, but rather as a necessary (and sometimes fruitful, sometimes frustrating) step in the professional process of trying to get a studio invested enough in your TV show to greenlight it. Ever since, I’ve always tried to have a “one for me” to work on whenever I’m working on a “one for them.”

A quick definition: a “one for me” under this rubric is a project that generated with me and is a story that I truly believe no one else would bring into the world. (Which is what I mean by “personal.”)

A “one for them” is any project that exists before I came on board (that is, a hired job), and/or one where I’m not truly in the creative driver’s seat, and/or one where there are a lot of voices weighing in on the creative direction.

I’m thankfully at a point of my career where I can be pretty selective, so any pre-existing project that I get hired for — that is, any “one for them” — is still always something I’m very excited about creatively.

But there is a practical difference between these two types of projects. A “one for me” type of project more or less lives or dies with me. On a “one for them” type of project, I can still bring a lot to the table, and I can shape the project enormously. But I can also be replaced and someone else can be hired to bring the project into being.

All that said, in my experience at least, there isn’t really a conflict between these types of projects. When things are going well, it’s more like they feed and enable each other.

For example, I started writing down the first images and thoughts of what would become Americana — my first movie as a writer-director and very much a “one for me” — while working on a “one for them” as a co-executive producer on The Terror: Infamy, a very fine show full of great, great people and run by an excessively kind showrunner, but a show that was nevertheless somebody else’s vision.

So as in Longmire, I once again needed to start a “one for me” project to be able to psychologically do a “one for them,” even if this “one for them” was actually a great job with great working conditions and cohorts.

But in addition to allowing me — I’m quietly (or not so quietly, maybe) a bit of a creative control freak with a big ego — the psychological space to work on a project where I’m not the front-and-center auteur, my “one for me” personal passion projects actually ended up benefiting from being written while I was doing these “one for them” hired gigs for someone else.

Because I was also doing a “one for them” while writing a “one for me,” I was less precious about these personal projects, more driven to make them entertaining and appealing, simply because I was in regular working contact with the kind of industry folk — mostly executives and producers — I would eventually need to believe in my passion projects in order to actually get them made.

I think I also ended up writing with more specificity and creative inspiration on these “one for me” projects simply because I was also in the middle of working directly with cast and crew members, the people who do their best work when given written material that inspires them. The “ones for them” helped me make my “ones for me” creatively stronger and more appealing.

Like everyone else in the WGA, I’ve been on strike the last 100 or so days, though I’ve spent just about all of that time in Arkansas instead of Los Angeles. One result of the strike is that I didn’t have any “one for them” type of hired gigs to work on over the summer. Instead, all I’ve had are “one for me” personal passion-type spec scripts to pound away at.

But even under these conditions, my thinking still kinda falls into a “one for them, one for me” mindset. Except maybe it’s more like a “one for TV” and a “one for features” mindset, plus a “one for a big budget studio director to helm” and a “one for me to direct that’s more of a lower-budget acting showcase” and a “one for a potential blue sky episodic procedural TV mystery that I would showrun.”

Now, I didn’t write five entirely new spec scripts this summer. But I did write a couple of them, each purposefully aimed at a different industry avenue for getting made. I also outlined several more spec script ideas, while also taking research notes for other ideas, and also working out some personal directing notes for other potential projects.

Most of these summer projects I hope to become “ones for me” — that is, very personally fulfilling, creatively unique projects. But some of them are designed to potentially also be “ones for them” — projects I’m still very creatively invested in, but that may also have a chance to break through commercially, or that at least have enough of a perception of creative viability to result in more substantial financial compensation for me than the “ones for me.”

Finally, when I’m at these early stages, I also think it helps for me to explain to myself what exactly is the nature of each project. And the “one for me” or “one for them” rubric comes into play here, as well.

Is this a “one for them” type of idea? If it is, then I can potentially pitch it as a commercially viable studio project and then get someone to pay me a good chunk of money to write it. If I do so, I’ll need to tailor the pitch primarily to executives and producers, who’ll be looking to balance creative instincts with financial realities. I'll need to foreground the most commercial elements of the project while also expressing the creative particulars that’ll make it feel original.

I’ll also need to accept going in that while such a project could potentially lead to a bigger profile and payday for me than a smaller project, it’ll also likely lead to much more compromise and could very well lead to me being replaced.

Or, is this a “one for me” type of idea? If so, then I’m probably better off just writing it for free. If I write such a script well, then I’m making a bet that it’ll become someone else’s passion project — a great actor or actress, primarily — and that this will be its path to getting made. To do this, I should probably foreground the project’s creative qualities, primarily making sure that the main roles are written in such a way that financially viable actors and actresses will be interested in them.

And unless I fall into a nightmare scenario, the smaller overhead of such a “one for me” project should mean much more creative freedom than a “one for them.” But, the financial upside of such a project will likely be limited, so I should also make sure to be lining up some financially-viable “one for them” type of gigs at the same time to make sure I can still pay the bills if I spend a year or more immersed in making one for me.

In an ideal world, I would be able to just knock out a string of “one for me” types of projects while also sending my kids to college. But how many people get to do that? Twelve? All in all, I think it’s pretty healthy to have a couple of fishing lines in both of these ponds. You never know which project is going to actually be the one that sells or gets made. And — again, just in my experience — both types of projects can strengthen the other.

Working on a very personal passion project can help keep you in touch with your inner muse and your best inner creative self while you’re writing a “one for them.” If nothing else, this backpocket “one for me” script can be a sort of personal firewall so you don’t become an interchangeable hack.

Working on a hired-gun or possible payday type of project can help keep you in touch with the practicalities of actually getting something greenlit and made in contemporary Hollywood while you’re writing a more personal “one for me.” If nothing else, writing for someone else can help keep you from getting too precious and crawling too far up your proverbial ass while romantically typing away on “one for me.”

Perhaps what I’m really gesturing towards here is my own Eastwoodian ideal: nudging my “for them” and “for me” piles closer together so they overlap enough to almost become indistinguishable from each other.

Hi Tony, thank you for the insightful and fascinating read! I'm an independent filmmaker just starting out in the business – my work in the ultra-indie scene has landed me representation, and with it an introduction to the "one for them, one for me" system you've described here. Truthfully, I've found this paradigm a bit confounding, and have been told my loglines are too "execution dependent", or otherwise lacking in immediate salability to pitch as a clout-less director with no mainstream industry credits. In racking my brain for more "commercial" ideas, I've found I keep returning to one difficult, almost stupidly simple question: what makes a film commercial in the first place? How does one write "commercially" while also maintaining enough creativity and ingenuity so as to make the film one with which you still connect? Perhaps this is too personal a question to be answered by anyone other than myself – and my apologies for wasting your time if that is the case – but your post here resonated with me and I thought it worth asking what you thought of all of this. Thanks again for reading, and for this article – you've got yourself a loyal new subscriber!

Your posts are gold; thank you for writing them. A couple questions: 1) Do you ever write and publish work as short stories (or some other genre) before attempting to sell/pitch them as scripts? The thing that kills me about the film industry (at least from my reading around) is how much stuff might get bought but never made. How to ensure that the stories you want to tell don't end up in limbo somewhere? That's why I'm wondering about writing/publishing in other genres first, like short fiction, and then adapting your own work -- so if it never makes it to screen, at least it exists in the world somewhere. 2) As an English lit prof with screenwriting aspirations, I really appreciate hearing about your trajectory. Going into tv required a complete break with academia for you; do you think it's possible to keep one foot in academia if the focus is on writing features? (Yes, I am trying to have it both ways; and yes, I submit that might be ridiculous. But I am always looking for a third path.) Appreciate any thoughts you might have on any or all of the above. Thanks again.