How to Create a Great Lead Character

identities and sub-identities and "x but also y"

Creating and writing interesting lead characters is more art than science. And in terms of creating characters, I actually think too much analysis ruins the romance and mystery that's needed to keep things interesting. Sort of like in a marriage. That said, sometimes some basic principles also come in handy.

My most basic principle: a character is only as interesting as the quality of scenes he or she lets me write.

That is, I can plan a great character arc or a great reveal or a great emotional payoff for a character in act three. But if that character leads me to write boring scene after boring scene in order to finally get to the payoff, it's not a great character. Or even a good one.

Helping you write interesting scenes isn't all a character has to do, of course. Especially not a lead character. But, if the scenes you're writing for your lead character are dull, then it doesn't matter what thematic depths or great evolutions you have planned for them. That is, don't get so enamored with your big picture intentions that you don't realize that a character isn't really working on a scene-by-scene basis.

Why? Because you're failing job #1: writing something interesting enough to reward a stranger's attention. It’s the easiest thing to forget, but no one owes you that attention. So we're not just establishing characters or motivations or storylines in our early scenes, we're also trying to convince our easily distracted reader to not put the script down and check their phone or pick up a different script. Any scene — especially early scenes, especially written by a non-established writer — can be that lethal put-the-script-aside scene.

When I'm creating a character, my most immediate pressing goal is to simply come up with some fake someone whose voice or personality or inner conflict is immediately so interesting that they allow me to write compelling scenes over and over again.

This means from the first scene onward. A very basic insight that has nevertheless taken me a few years to fully realize. One of my own weaknesses: a desire to peel back layers of the character onion too slowly. In terms of storytelling, I like gradual reveals, where characters give a certain first impression but reveal unexpected depths or motivations or shadings later. It’s a staple of westerns and samurai films — my two favorite genres — and I'm a total sucker for it.

Early in my career, though, I'd often end up erring on hiding all the most interesting aspects of a character in my back pocket. That is, I'd introduce the most boring version of a character up front in the hopes of complicating them and making them more interesting later. Not the best strategy for hooking a reader! I had to learn how to introduce a more interesting version of my characters up front, while still holding onto some secrets to reveal down the road. Again, more art than science. But first I had to recognize that I couldn't hoard all of a character's interesting traits and secrets for later reveals. I had to be a bit more generous a bit earlier to my reader.

Before I get into the nuts and bolts of this one particular practical character-creating idea I have, I want to be clear: I don't actually create characters with some specific strategy in mind, let alone some kind of template. I usually get enamored with an image, or a voice, or a scene, or a dilemma. And then I usually just write and daydream and sketch and trial and error things out until something takes shape. I’ll make playlists and go for walks and imagine my characters doing cool shit to cool music. And it's not until I've written a series of interesting scenes that I even know if I've got a character worth writing. It's an unremarkable, largely organic process.

This might be why, all things even, I'll prefer to write scripts on spec (for free and on my own) than to get paid up front to develop them with other people. It's not that I'm anti-collaboration. I think it's largely because, in the development process, you often go from some big picture idea to a beat sheet to an outline, and then only after all of this do you finally go to writing the script. Which means finally writing scenes.

Now, that particular process makes sense for those producers and executives developing projects with me. They want to know up front what they're paying for. Totally justified. But for me as the writer, this process often means that I'm building the edifice for an entire story without really testing whether or not my characters are compelling and conflicted enough to even make a handful of scenes interesting, let alone an entire script.

When I'm writing on spec, my process is different than when I develop. Left to my own devices, I'll come up with some key story idea or logline. Then I'll often write a few early scenes to get to know the characters. Not just know the characters, but to see how they sound and how they behave and to let those qualities play off of each other. I write and revise these qualities until they result in interesting-to-me scenes.

After doing this, then I'll usually return to the outlining stage, but now armed with much better intelligence about my characters. And that's when I'll finally plan out the narrative. Actually I usually just plan out 1/2 to 2/3 of it, because I like to have room to make discoveries.

After making those big picture plans, then I return to writing scenes again, knowing where I'd like the story to go. Often, I'll keep toggling back and forth between big picture ideas and scene-by-scene grunt work, revising and rethinking both sides as I go, letting each side of that equation inform the other. I find this to be a pretty fruitful approach, but it's not an approach that's particularly conducive to the preferred more streamlined development process of producers and executives, who like to know what they're getting up front.

What I'm mostly getting at is this: for me, character is tied to voice. What makes a character interesting — in the big picture — is usually what they want.

But what makes a character interesting on a scene-by-scene basis — aka, how they're actually experienced by a reader or viewer — is how they pursue what they want. What they talk about. What they avoid talking about. How they use words to mask their intentions, or to distract or injure or seduce others. What decisions they make from moment-to-moment. And you can usually only know this by putting your characters into actual scenes.

Now, this isn't always the case. In many strong genre films, the story isn't really about the protagonist or their voice so much as the situation they find themselves in. So you can have just an okay character anchoring a great genre film as long as the situation is compelling, the performer is charismatic, and the genre thrills are amazing. But unless you have Jackie Chan performing in POLICE STORY, or Jamie Lee Curtis fighting for her life against Michael Myers in HALLOWEEN, you're usually going to want a complicated, innately compelling character to carry your script.

Great, you’re probably thinking. So, how do you actually make an interesting character? Again, more art than science. If I truly had the secret recipe, I'd be a pretty famous screenwriter instead of a pretty anonymous working one. But, here's something I've noticed about a lot of strong lead characters, especially in post-THE SOPRANOS cable television. They often can be described as this:

x, but also y

For many of the lead characters in prestige type TV shows, there's some key conflict either within the character, or in the split between who they are and who they present themselves to be. And that's what drives their story.

Usually their public identity — their "x" — is a somewhat familiar and time-tested archetype. But their sub-identity — their "y" — is more of a storytelling novelty.

Some examples: Tony Soprano is a mobster (x), but he's also suffering panic attacks and seeing a therapist (y). Walter White is a pushover high school teacher (x), but he's also got cancer and begins cooking meth to make money (y). Carrie Mathison is a CIA agent (x), but her bipolar condition causes people to distrust her (y). Don Draper is a successful advertising executive (x), but his entire life is predicated on stealing another man's identity (y). Barry Berkman is a hit man (x), but when he moves to LA he discovers that he wants to become an actor (y). You get the idea.

There’s a bit of a pattern here. Big identity (x) and insurgent identity (y). Something familiar (x) meets something unpredictable and novel (y).

Now, you can take this formulation to a point of absurdity. Daisy Kaleidoscope is a talk show host (x), but she's also a serial killer of clowns (y). Or Jojo McIntosh is a librarian (x), but he also masturbates in front of pigeons (y). So, there's limits. But I think this "x but also y" type of characterization can be quite effective if:

1) x and y are in dramatic conflict

2) that conflict illustrates something thematically interesting.

Tony Soprano's gangster status and his neuroses are dramatically interesting because each side of his equation inverts expectations: about how gangsters behave, and about the types of men who seek therapy. And in combination, these gangster and neurotic sides of Tony Soprano also seem to suggest something thematically interesting about the American male psyche at this stage of national decline.

Likewise, the dynamic between Walter White's two sides suggests something interesting about the simmering resentments lurking under the mask of the domesticated, well-behaved middle class American male. Or Don Draper's material success and his false identity suggest something about the fictions and deceptions underpinning the capitalistic American dream, etc.

But any bright high school sophomore can point out a theme about the dangers of empire or racism or toxic masculinity or whatever. That's easy. TV commercials and blue check journalists and pundits on twitter are throwing out big brain timely themes all the time.

What's much harder is simply writing interesting scenes. Scene after scene, episode after episode, season after season. But it's nearly impossible to write interesting scenes with boring characters who speak in generic voices. Their scenes can be active and tense. But probably not interesting.

Let's look at THE SOPRANOS, the best TV show ever made. I am never, ever bored by a Tony Soprano scene. Lots of that is Gandolfini, my GOAT. But also, in all of Tony's scenes, his "x" and his "y" are always playing off of each other in dramatically interesting, unpredictable ways.

Actually, all this "x" and "y" shit doesn’t even do justice to Tony Sopranos' complexity. He has one identity with his mafia bros. Another at therapy. Another one at home w/ Carmella, AJ and Meadow. Another one with his mom. Another with his goomar. Etc.

So that's kinda interesting. But what's really interesting is when these identities converge. When Tony's mafia side leaks out during therapy. Or his traumatized little boy side leaks out at the Bada Bing. Or his newest therapy breakthrough leaks into a scene with Uncle Junior.

This unstable multi-masked personae of Tony Soprano always gives the writers, and Gandolfini, interesting conflicts to stage in every scene. Tony's never just one static thing. You watch and wonder: which aspect of his personality is going to be dominant in this scene? How is that going to play out once he gets home? At work? And so on. You lean in to find out, scene after scene, hoping for the best but fearing the worst.

To me, that's the genius of the show. Not only does Tony Soprano have these many sides, but he's always surrounded by characters and situations that pull forth sides of his personality he wants hidden, or that put those sides into conflict at inconvenient moments.

So it's not enough to just have an "x, but also y" sort of character. These identities, or masks, or sides need to be in constant dramatic conflict and have real thematic consequence. And your character needs to repeatedly be placed in situations where you don't know which side of their identity will be dominant.

Let's say you have a procedural pilot where your lead character is a homicide detective (x) but he also has a hidden sex addiction (y). Kinda boilerplate, but okay. But simply having the "x but also y" construction won't necessarily make this character interesting in the slightest. Why? Because if that detective is just a cop during his investigation scenes, and just a sex addict in his personal scenes, then where's the inner conflict?

That character's x and y aren't competing against each other jostling for dominance on a scene-by-scene basis. They're just taking turns in the spotlight. And you also still have to find a connection between homicide investigation and sexual addiction that makes them thematically related, or else it'll just feel hollow. (Most likely, to make a character like this work, the detective probably has to be specializing in crimes of a sexual nature while also dealing with his secret sex addiction — that way, his “x” and “y” aren’t just taking turns in the spotlight, but are in deeper conflict, with each side of the equation dramatically informing the other side. Perhaps he’s equally aroused and repulsed by the crimes he’s investigating and is having a crisis because he doesn’t know which side of his identity has motivated his career in this line of work, etc.)

Like I've said, I don't go into scripts with this "x but also y" construction in mind. And a lot of characters I come up with don't fit it. But it's a pattern I've seen in my own work, and in work I admire.

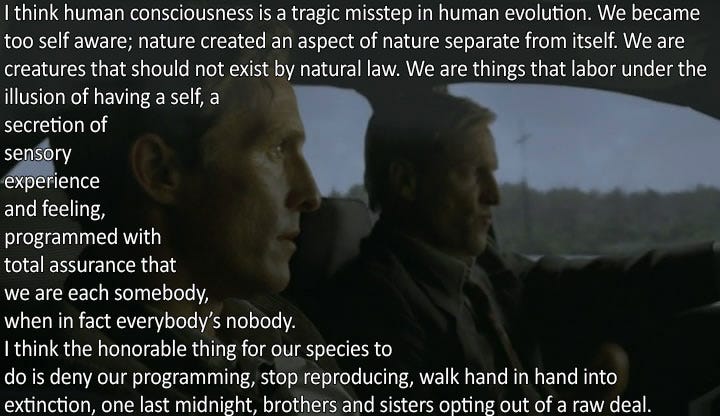

One last example: in TRUE DETECTIVE, Rust Cohle is a gifted homicide detective (x) who devoutly believes in his own homegrown sort of nihilistic philosophy (y).

We’ve seen gifted homicide detectives before. They’re a staple of that genre. But we haven’t seen many gifted homicide detectives with a Rust Cohle outlook on existence. And this novel combination of detective-philosopher makes Rust speak and behave in a very interesting manner. I’d argue that this novel combination also makes us see thematic connections between the crime procedural, hard-boiled fiction, anti-natalist philosophy, and the role of flawed men in a fallen social order that we might not otherwise consider.

But most importantly, I think this novel conception of Rust Cohle — his insights and layers and inner conflicts — makes typical procedural cop scenes instantly fascinating. Suddenly, it's not just a ride-along between partners, it's a ride-along with Rust Cohle. It's not just an interrogation, it's an interrogation with Rust Cohle. It's not just a double-date, it's a double-date with Rust Cohle. And that makes all the difference.

Because of this one character's very well-defined unpredictability, all of these should-be-familiar scenes are now unpredictable and fascinating. Rust's identity as a homicide detective (his x) places him in a familiar genre and in familiar scenes within that genre. But his very unique sub-identity as an autodidact anti-natalist philosopher (his y) suddenly makes his behavior within these familiar scenes totally unpredictable, which therefore makes the scenes themselves unpredictable.

Rust Cohle's creator, Nic Pizzolatto, wrote the TRUE DETECTIVE pilot as a literature professor in Indiana. It's one of the scripts that actually helped Nic break into the entertainment industry and quit academia. This conflicted, uniquely voiced homicide detective-philosopher Rust Cohle character he created — again, as an outsider — lured Matthew McConaughey to do TV back when movie stars didn't do such things. (Especially not with first time showrunners.) McConaughey’s attachment to the project then lured in his buddy Woody Harrelson. Which then caused a bidding war which caused HBO to order the whole thing to series with Nic as showrunner. And so forth.

This chain of events all started off with an industry outsider inventing a single character who had a familiar, time-tested "x" — gifted homicide detective — but who had a "y" that no one had seen or heard before. Now, that's not all the show had to offer, but I'd argue that that was the main building block.

Obviously, this "x but also y" idea isn't the only way of thinking about your lead character. More art than science, etc. But, creating a lead character with a familiar, time-tested public identity but a very novel and fascinating sub-identity can lead to you creating a character with a well-defined inner conflict. And a character with a well-defined inner conflict will likely make it much easier for you to write a single interesting, original scene for him or her.

And if you can do that — write just one truly interesting original unpredictable scene with a uniquely compelling lead character at the start of your script — then you're already way ahead in this game. Now you just have to do it over and over and over again.

Subbed to Substack because of this post. Working on a pilot that I want to start writing but know it's not ready. And this is the exact reason. I know the plot and the reveals and the overall arc and it feels great. But I don't know who my main character is yet aside from a vessel for the plot. Going to come back to this post for some refreshments on my journey to discovering who he really is. Thanks!

This is great stuff. I'm grabbing it. Thanks!